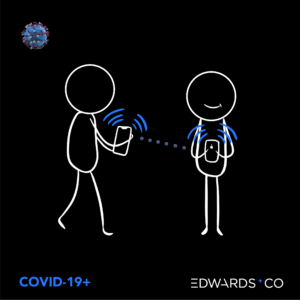

As that famous virus continues to dominate world affairs, governments and tech companies worldwide are turning to mobile technology to help track person-to-person virus transmissions. Singapore, the UK, China and Australia have all developed mobile apps that are being downloaded on a mass scale, whilst Apple and Google are engaging in an unprecedented collaboration to create a Bluetooth-based contact tracing platform. These applications have great medical potential to reduce the rate of infections, and downloading them are almost inarguably in the interests of public health and the greater good. However there have been worldwide concerns about their privacy implications. This article looks to Australia’s COVIDSafe App specifically and examines it in the context of Australian privacy law.

On 26 April 2020, the Australian Government released the COVIDSafe App. It has gained real and rapid traction, with over 5.87 million Australians having downloaded it as at 20 May 2020 (Source: Guardian). The app has been developed for both iOS and Android phones.

The official purpose of the COVIDSafe App is to support contact tracing processes currently being undertaken by State and Territory health officials to identify persons in Australia who have potentially come into contact with someone who has tested positive for the virus.

In order to be effective, Health minister Greg Hunt forecasts that at least 40% of Australians need to download and turn on the COVIDSafe App.

When using the COVIDSafe App, the software records data including an encrypted user ID, the date and time of contact, and the strength of the Bluetooth signal when other COVIDSafe users are within the user’s proximity. The encrypted user ID is created every 2 hours, and is logged in the National COVIDSafe data store that is operated by the Digital Transformations Agency (‘DTA’) in the event the user needs to be identified for contact tracing. The data store is a cloud-based facility that uses infrastructure located in Australia.

Unlike some countries such as the US (where it is enshrined in the Constitution), Australia does not have an absolute right to privacy (see: Victoria Park Racing and Recreation Grounds Co Ltd v Taylor (1937) 58 CLR 479).

Instead, the Commonwealth’s Privacy Act 1988 (‘Privacy Act’) broadly governs laws and regulations related to privacy, and provides protection to individuals. An individual alleging a breach of privacy can complain to the Australian Information And Privacy Commissioner, who has a range of investigation and enforcement powers.

Schedule 1 of the Privacy Act includes the Australian Principle Principles (‘APP’), which govern the standards, rights and obligations surrounding the collection, use and disclosure of personal information and the rights of individuals to access their personal information. These principles as considered to be the cornerstone of the privacy protection framework provided by the Act.

Since the release of the COVIDSafe App in Australia less than a month ago, much has been written in the mainstream media about potential privacy concerns. No doubt it has been the subject of debate by Australians around virtual water-coolers or from a safe distance of 1.5 metres. At its most basic, this relates to concerns with sharing information with the government, and what uses might be made of that information. To some, the concept of ‘Big Brother’ monitoring movements is evocative of sci-fi thrillers, where a powerful State micro-chips its citizens or takes other action at the expense of personal liberties, ostensibly in the interests of the greater good.

Scene from Stanley Kubrick’s, A Clockwork Orange, 1971.

The reality is that the Government already has access to great troves of personal data about its citizens, and is relied upon, in a democracy such as Australia, to handle such information responsibly and in line with transparent laws and regulations. With respect to the COVIDSafe App, certain additional operational and regulatory mechanisms have been introduced to safeguard privacy. Further, the vast majority of Australians have a Facebook or Google account, and are already yielding up great quantities of potentially sensitive personal data to these tech giants.

To address privacy concerns involving the COVIDSafe App and provide additional protections under the Privacy Act, on 14 May 2020 the Federal Parliament passed the Privacy Amendment (Public Health Contact Information) Bill 2020 (‘COVIDSafe Laws’). This legislation introduces a number of new measures, including:

COVIDSafe’s Privacy Policy sets out the kind of data collected by the COVIDSafe App, how it is used and the security measures that protect it. According to the Policy, the COVIDSafe App requests a user’s phone number, name (which may be a pseudonym), age range and postcode.

In order for this information to be ‘personal information’ within the meaning of the Privacy Act, the individual must be reasonably identifiable from such information, or by combining that information with other datasets to which the collector of the data has access. However, the COVIDSafe Laws have avoided this debate by expressly classifying COVIDSafe App data as ‘personal information’.

To increase compliance with privacy laws, COVIDSafe has introduced a number privacy features, including the following:

The independently developed Privacy Impact Assessment details the COVIDSafe App’s compliance with the Privacy Act and the APP, which has been made publicly available. Part D of this Privacy Impact Assessment dissects the COVIDSafe App across the 13 APP principles. The report finds that, whilst further work is needed to address some privacy risks, the COVIDSafe App is overall compliant with each of these principles.

Despite the App’s compliance with privacy laws, a number of bodies have identified privacy risks involving the COVIDSafe App. For example, the University of Melbourne maintains that:

‘even though the data logs are only sent to the Central Authority following user’s consent, there is no check to ensure that the request from Central Authority is genuine or not, i.e. whether that user was in proximity of an infected user’[1]

This essentially means that any Central Authority is given the ability to obtain and decrypt the data logs at will. The University of Melbourne also highlight that, despite the application’s policy that data logs on the handsets are deleted after 21 days, ‘there is no guarantee that the data logs decrypted at the Authority server would also be deleted’.

The UNSW Law School further argues that the App raises concerns relating to its lack of transparency and flaws in its protections.

The Australian government has sought to address these concerns by introducing the COVIDSafe Laws discussed at high level above. The DTA also released the App’s source code on the 8 May 2020 to address transparency concerns, and is currently open to community feedback on its operation and security.

Whilst COVIDSafe seems to be compliant with Australian’s privacy laws, and new and specific COVIDSafe Laws have been introduced to mitigate privacy concerns, a number of bodies maintain that privacy risks still remain. In a world where digital platforms such as Apple and Google already access large amounts of sensitive personal information about users, people are right to remain vigilant about exactly what they are yielding up.

Importantly, under the COVIDSafe Laws, it is illegal to force anyone to download the COVIDSafe App. This is not a Stanley Kubrick film; the choice about whether to adopt the COVIDSafe App is a personal one for each Australian. We are however living in extraordinary times, and these applications have the potential to unlock the power of digital in the interests of public health generally.

Edwards + Co Legal is a commercial law firm assisting businesses in NSW and across Australia. We are closely following the new business laws and regulations that are being developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article is part of our “law in the time of corona” series of business law articles.

[1] https://eng.unimelb.edu.au/ingenium/research-stories/world-class-research/real-world-impact/on-the-privacy-of-tracetogether,-the-singaporean-covid-19-contact-tracing-mobile-app,-and-recommendations-for-australia