Ashley Madison (www.ashleymadison.com) styles itself as “the most successful website for finding an affair and cheating partners”. As at 25 August 2015, it claimed to have over 39 million members, though there have also been suggestions that these figures have been artificially inflated.

In August this year, the quiet outrage of millions of exposed members of the Ashley Madison website echoed around cyberspace, as it emerged that their personal information had been made publicly available on the net.

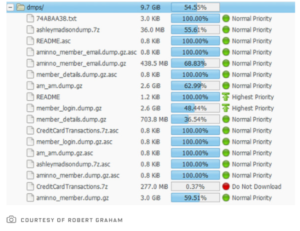

Here’s a snapshot of what some of the early data looked like[1]:

The Deep Web and various Torrent file-sharing services soon disgorged data sets close to 10 gigabytes in size, revealing the names, addresses, phone numbers, emails, member profiles, credit card data and transaction information.

According to general reportage in new and traditional media, ‘The Impact Team’ had threatened to post user details online unless Avid Life Media shut the Ashley Madison service down. The ‘hackers’ argued that their actions were a defensible form of ‘white hat hacking’, perpetrated as a form of retributory protest against the lack of security measures on the site.

A white hat hacker is a computer security expert who breaks into protected systems and networks to test their security. White hat hackers use their skills to improve security by exposing vulnerabilities before malicious hackers (known as ‘black hat hackers’) can detect and exploit them. Although the methods used are similar, if not identical, to those employed by malicious hackers, white hat hackers usually have permission to employ them against the organisation that has hired them[2].

However, The Impact Team did not have the permission from Avid Life Media management, so referring to the act as white hat hacking is not correct.

As republished in the Sydney Morning Herald on 22 August 2015, The Impact Team said: “We were in Avid Life Media a long time to understand and get everything… Nobody was watching. No security[3].”

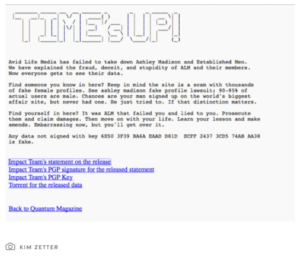

When the company failed to shut down the service, the hackers started to publish the users personal information. But not before they posted this message[4]:

In some ways it is hard to imagine more explosive information being posted online in such volume. In this case, it was not only the size of the big data trove, but what Avid Life Media did with it.

The disclosure of Ashley Madison data highlights a number of interesting legal questions for us in Australia:

We consider these points further below.

An illustration of the international cause of action for invasion of privacy occurred in Milan, Italy, in 2010, where an Italian court convicted three Google executives of invasion of privacy for failing to take down a Youtube video that showed a disabled child being bullied.

In the Google case, David Drummond, Google’s senior vice-president of corporate development and chief legal officer, Peter Fleischer, global privacy counsel, and George Reyes, a former chief financial officer, were found guilty after a video of Italian teenagers bullying a youth with Down’s syndrome was uploaded to Google Video.

Similar causes of action are able to be brought in other countries, including the USA, the UK and France and Italy.

However, in Australia, there is no cause of action for invasion of privacy that is able to be brought in a court of law. Instead aggrieved plaintiffs must have recourse to alternative causes of action, such as:

Under Australian law, a person acquiring information in confidence has a duty to maintain that confidence:

“It is a well-settled principle of law that where one party (‘the confidant’) acquires confidential information from or during his service with, or by virtue of his relationship with another (‘the confider’), in circumstances importing a duty of confidence, the confidant is not ordinarily at liberty to divulge that information to a third party without the consent or against the wishes of the confider.”

(Attorney-General v Guardian Newspapers [No. 2] [1998] 2 WLR 805)

Uniform laws introduced across Australia’s states and territories in 2006 serve to protect individuals from the publication of information that diminishes their reputation, though there exist a number of defences, including that the information was true.

In addition, under the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth), the Australian Privacy Commissioner is empowered to take action in the Courts, including the imposition of fines on organisations of up to $1,700,000.

As a general principal, the Privacy Act regulates entities that carry on business in Australia (see section 5B(3)(b))[5].

Further, following amendments from March 2014, websites that collect personal information in Australia are deemed to be a business carried on in Australia for the purposes of the Privacy Act. This includes businesses that collect information from an individual who is physically in Australia, even in situations where that business is incorporated outside of Australia and the website is hosted outside of Australia[6].

As Avid Life Media collects information of Australian members, it seems clear that Avid Life Media would be deemed to be carrying on business in Australia for the purposes of section 5B(3)(b) of the Privacy Act. On 20 August 2015, the Office of the Australian Information Commission (‘OAIC’) revealed that it had commenced investigating whether Avid Life Media met its obligations under the Australian Privacy Act to take reasonable steps to ensure the security of its customers’ personal information.

From 12 March 2014, where an entity has contravened a civil penalty provision, the Commissioner can apply to the Federal Court or Federal Magistrates Court to enforce a civil penalty order. If the Court finds on the balance of probability that a breach has occurred, the Court can order the breaching entity to pay the Commonwealth the penalty.

Whilst the civil penalty provisions are primarily focused on credit reporting entities – which Avid Life Media is not – the penalty provisions can extend to organisations generally, where there are ‘serious or repeated’ interferences with privacy rights.

New section 13G of the Privacy Act relates to ‘serious or repeated interference with privacy’ and carries a maximum penalty of:

The Law Reform Commission has cited examples of serious or repeated interference with privacy as potentially including things such as:

The third category above is most relevant in the present case, though perhaps the average Australian who has had their privacy compromised through a site connecting people for illicit affairs may be reluctant to complain.

Also, where an entity that holds private information suffers a breach through causes beyond its immediate control (such as where its customer database is hacked, as in the case of Ashley Madison), even where personal information of a large number of individuals is compromised, this would not necessarily be regarded as “serious” for the purposes of the civil penalty provisions.

At least in part, it seems that the matter will turn on whether the entity has taken reasonable security precautions. Third party hacking may indeed be somewhat beyond an entity’s control, however if it occurs because of failure to implement a normal industry security precaution that would be likely to be looked upon poorly by the Commissioner.

Clause 9 of Ashley Madison’s privacy policy, states:

“We treat data as an asset that must be protected against loss and unauthorised access. To safeguard the confidentiality and security of your PII, we use industry standard practices and technologies including but not limited to “firewalls”, encrypted transmission via SSL (Secure Socket Layer) and strong data encryption of sensitive personal and/or financial information when it is stored to disk.”

Through Australian Privacy Principle 11 (‘APP 11’), the Privacy Act requires entities to take “active measures” to ensure the security of personal information they hold, and take reasonable steps to protect the information from misuse, interference and loss, as well as unauthorised access, modification or disclosure.

Generally speaking, as the amount and/or sensitivity of personal information that increases, so too does the level of care required to protect it.

A case in point was where, almost immediately upon the new Australian Privacy Principles coming into effect, Telstra was fined $10,200 by the Privacy Commissioner after inadvertently exposing the personal information of 15,775 customers to publicly accessible Google search. The data included customer names, telephone numbers and in some cases addresses. It also included 1,257 silent line customers[7]. Under the Privacy Act, even where the hosting of the personal information is outsourced to a third party (such as Amazon Web Services) the outsourcer is still deemed to be handling the personal information and responsible for it.

To assist organisations with its obligations under APP 11, the OAIC is currently consulting on its draft ‘Guide to developing a data breach response plan’ which aims to inform organisations about what can be done ahead of time to ensure effective management of a privacy breach, should one occur.

Unless the Impact Team “carries on business in Australia” (discussed under part 3.2 above), it may not be regulated by the Australian Privacy Act.

However, under breach of confidence principles in Australia, a person who comes into possession of confidential information has a duty to maintain that confidence:

“…equity may impose obligations of confidentiality even though there is no imparting of information in circumstances of trust and confidence. … The nature of the information must be such that it is capable of being regarded as confidential. A photographic image, illegally or improperly or surreptitiously obtained, where what is depicted is private, may constitute confidential information.”

(ABC v Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd (2001) 208 CLR 199)

Based on the above, the Impact Team could be liable for breach of confidence under Australian law for disclosing confidential information of Australian users.

The increased risks surrounding data security combined with the enhanced privacy legislation has seen a rise in the number, and a broadening in scope, of cyber insurance policies in Australia.

These policies differ by provider, and cover a wide range of protections including, most relevantly for this discussion, third party claims for failing to keep data secure, reimbursement for damage done by hackers, reimbursement of costs to remedy a breach and cyber extortion.

Generally speaking these kinds of policies together with director and officer type insurance, would stand behind civil penalties for breaches of the Privacy Act. This is subject of course to any limits and conditions in the terms of the policies themselves.

It also bears remarking that no insurance policy can protect an organisation from the reputational damage caused by inadequate data security and privacy policies.

The Ashley Madison exposure was made possible by the perfect storm of our era of ‘ultra connectivity’, where the power, ease, ubiquity and virility of web-based services combined with the ‘wisdom of crowds’, to create an environment in which millions of global online users blindly trust strangers with their personal information.[8]

[1] See http://www.wired.com/2015/08/happened-hackers-posted-stolen-ashley-madison-data/

[2] See www.techopedia.com/definition/10349/white-hat-hacker

[3] http://motherboard.vice.com/read/ashley-madison-hackers-speak-out-nobody-was-watching

[4] http://www.wired.com/2015/08/happened-hackers-posted-stolen-ashley-madison-data/

[5] While the definition of “carries on business” is not defined in the Privacy Act, other areas of the law provide guidance on what is meant by this. For example, an entity that conducts the bulk of its business outside of Australia and does not have a physical business location in Australia, can still be deemed as carrying on business in Australia (Gebo Investments (Lauban) Limited v Signatory Investments Pty Limited [2005] NSWSC 544 [39].)

[6] Explanatory Memorandum, Privacy Amendment (Enhancing Privacy Protection) Bill 2012, p 218.

[7] See http://www.itnews.com.au/news/telstra-breached-privacy-act-by-exposing-user-data-374722#ixzz3r4O4ZaGd

[8] The mobile application, Tinder, illustrates this trend. Launched in September 2012, by March 2015 was reported to have 50 million worldwide users (Source: http://expandedramblings.com/index.php/tinder-statistics/).

The information above is general in nature. If you would like to learn more about data and privacy law, please contact us below.